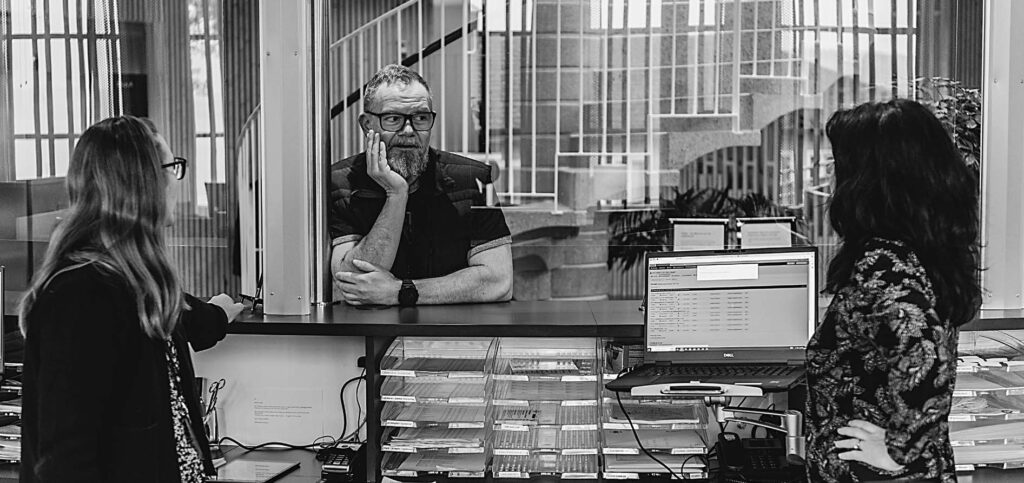

Problems are there to be solved, and sometimes a problem needs to be redefined for the right solution to be put in place. These are the words of Tony Gorschek, Professor of Software Engineering at Blekinge Institute of Technology, who regards working with companies as a matter of course. This also pinpoints the difference between being a researcher and a consultant – a difference that collaborating researchers often feel they need to clarify.

For Tony Gorschek and his colleagues, collaboration is about making a difference and creating value for both the business sector and academia. In a way, collaboration could be described as a lifestyle, perhaps also associated with a certain type of personality. Yet it also involves being in an environment, like the one Tony works in, where collaboration is a natural element and is seen as a prerequisite for the development of Sweden and the region. Despite its geographical location and rather modest size, Blekinge Institute of Technology has managed to put software engineering on the world map and attracts researchers from all over the world. The attraction is not high salaries, but rather the proximity to practitioners and the close relationships with companies in the region that the research group has built.