The Stockholm School of Economics (SSE) is an example of an institution entirely founded on collaboration – although the word collaboration is neither used nor part of their vocabulary. According to President Lars Strannegård, the idea of doing things together with companies and other stakeholders permeates the way SSE organises itself to conduct relevant teaching and research. It is in dialogue with others that SSE develops knowledge pertinent to our society.

Lars Strannegård: Art as itching powder

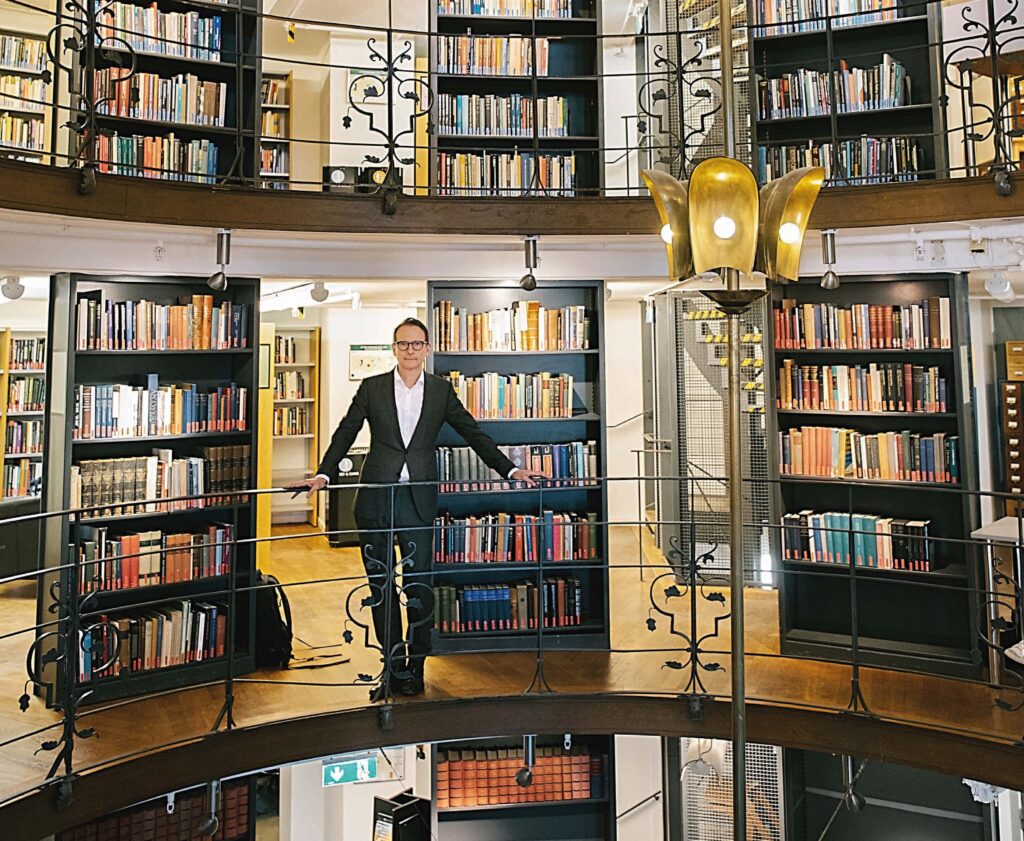

When we enter SSE through the grand oaken doors on Sveavägen, we are greeted by a buzz. It is clear that students want to spend their time here. While the oak entry symbolises the way into their studies, students have all the more doors to choose from after graduation, out to all corners of society. Today the imposing 1925 building, designed by Ivar Tengbom, is filled with art, with the aim of providing a type of intellectual itching powder that raises questions and encourages conversation and reflection, even after graduation.

As may be expected from a social sciences researcher – in this case a professor of business administration specialised in organisation and leadership – Lars Strannegård responds to our initial question with a question of his own. He wants to problematise the concept. SSE has the stated ambition to cultivate students’ ability to pose questions and approach a problem from various perspectives. Perhaps it is because collaboration is so self-evident at SSE that the word does not occupy strategic policies, specialised services, or advisory bodies. Instead, Lars wants to talk about the importance of having conversations – pursuing dialogue for knowledge transfer and learning – with different societal actors, and especially with the companies that help fund SSE.

115 years of confidence

If researchers are rooted in the role science fulfils in society, talk about collaboration need neither be so anxious nor so complicated. SSE’s long history creates stability and self-confidence that allows SSE to both listen to society’s needs and offer the solid, relevant knowledge that society demands. If SSE adapts too much to what the outside world wants, it will not be relevant in the long term, Lars concludes.

This is from my perspective and that of SSE, and we’ve after all now had 115 years to build up this credibility and legitimacy. I don’t know how much of this is transferable, but this is still what I think important. You have to believe in the academic knowledge production model and have confidence in that model – and we do.

SSE is often described as an elite university where “the best seek out the best”. This is also reflected in the companies that want to contribute to SSE. During his tenure, Lars has managed not only to attract new partners, thereby significantly increasing SSE’s budget, but also to interest other societal actors. In the cultural sector, Lars has also been portrayed as a “visionary economist” who can speak to the intrinsic value of art beyond financial gain.

Since Lars took over as president, SSE has also invested in bringing art into education – as a kind of itching powder to remind about and teach the importance of reflection as a gateway to knowledge. This approach is summed up by the Art Initiative, which includes a number of schemes. SSE’s premises on Sveavägen in Stockholm is now also a bit of an art institution, with its installations and artworks as well as lecture halls decorated by various artists.

Education and art are two sides of the same coin, and therefore both scientific and aesthetic forms of knowledge are needed. In this way, tomorrow’s decision-makers are also prepared to meet the societal challenges we face, and can help bolster Sweden as a leading knowledge nation. Lars believes that raising the level of self-cultivation or Bildung is important not only to strengthen Sweden’s competitiveness and ability to innovate, but also its democracy through the safeguarding of free thought.

Academic freedom

If researchers are to be relevant, they must have integrity and should not slip into consultancy roles or view their research as a kind of commission. They must stick to scientific principles. This also strengthens the legitimacy of researchers. If these principles are compromised, it will no longer be possible to attract the best researchers nor the best students. Lars believes that it is also important to have integrity and be clear about what SSE can and cannot offer in partnerships. There is a well-established model for organising collaborations with companies and other stakeholders, and it is trusted by all involved.

Academic freedom is always enshrined in all agreements with external parties. It is the premise of all collaborations: “Academic knowledge production is always at the core.” It is also crucial to attract the best researchers, i.e. those who, according to Lars, are willing and able to publish in highly ranked journals that require theoretical contributions. At the same time, research is expected to be socially relevant, and in recent years SSE has invested in centres focusing on different sectors or societal challenges. These can be understood as collaborative units that serve as meeting places for ongoing dialogue between researchers, students, and companies with the aim of creating a mutual understanding of what is relevant.

However, the research itself is not necessarily conducted in collaboration. Unlike at many other universities, specific collaboration agreements are rarely, if ever, signed at the project level. Instead, researchers engage external parties in various forms of dialogue, both to listen to the reality of companies and to share their research. Making knowledge available is also an activity beyond partner companies – not least to reach other sectors of society. SSE for instance recently launched the SSE Research Hub, a portal making it easier for the public, experts, and the media to find research and researchers affiliated with SSE.

Everyone cannot be jacks-of-all-trades

Collaboration can easily become bureaucratic, but it doesn’t have to be more complicated than having respectful conversations, says Lars. For Lars, it is about conversations aimed at transferring knowledge and learning from and about each other. A certain degree of organisation is required, he argues, but it must not be suffocated by administration that takes the focus away from the profession and the scientific principles. Part of making this work and ensuring the availability of time and resources for ongoing dialogue with partner companies and other stakeholders is that no single person can do everything – individual researchers cannot be jacks-of-all-trades and do everything, Lars reasons.

Lars explains that this is why, when seeking funding for new ventures, they always include both a scientific director and an executive director. While the former focuses on the scientific work, the latter, often also a researcher with a PhD, is responsible for managing contacts, listening to needs, and acting as a facilitator. This arrangement gives the individual researcher time and space to focus on their research.

The various centres have associated advisory boards. Once a year, and sometimes more often, researchers, company representatives and students meet to discuss the problems they are grappling with, the most topical issues, and the type of skills needed. Lars describes these discussions as eye-openers for the students, who often are under the impression that companies’ everyday business involves pricing, margins, and IT, and much more seldom major global issues such as the Suez Canal, sustainability, or conflicts in the world.

The point is that we should understand their reality. The conversations act as a kind of lubricant between the companies, but also between the companies and the students, and between the companies and researchers.

The conversations facilitate mutual understanding and aid mutual learning, which all parties participate in and contribute to. SSE regards listening to each other as crucial in being relevant. Lars himself participates in these conversations, and perhaps this is another factor in their recipe for success when it comes to attracting new partner companies.

If companies don’t perceive what we do as relevant, we can wave our business goodbye. There’s something in this buzz phrase – that it is part of our DNA – because it really is.

Olika kunskaper behövs

Listening to and understanding the realities of the world around us involves valuing different experiences and types of knowledge. Everyone is needed, Lars notes. Not everything is about episteme, i.e. calculations, logical thinking, and the ability to draw conclusions – knowledge that can be documented and transferred, for example through lectures and course literature. Equally important is techne, i.e. practical knowledge that is not as easily transferred into text, which means that something is created at the same time as the knowledge is practised. Lars, who also wrote the book Senses of Knowing, explains the idea of scientific knowledge production, and says that much starts with the view of knowledge. Before each new partnership, what SSE does and stands for is explained. This is described in the acronym FREE – emphasising Facts, Reflection, Empathy, and Entrepreneurship – and what should be regarded as a mission to be a world-leading business school.

A basic requirement in SSE’s partnership agreements is long-term relationships and the realisation that different types of knowledge are needed, with companies contributing to research and education in a way that is relevant to all parties. Referring to Bruno Latour, Lars describes the still widespread image of how knowledge is produced: A genius comes up with something, which is then translated from basic research into application and innovation, and subsequently successfully disseminated and used in society. Yet reality is rarely that linear or all that clear. Instead, as Latour writes, the first idea “barely counts” – it is more like a thought, “and then it starts to unravel and you discuss it together, and then something comes of it”.

The students are crucial in that unravelling. Teaching acts as a kind of cogwheel for the development of new thoughts and ideas. Lars believes that students’ significance is often lost and they tend to end up outside “the collaboration model”, but they are just as important to highlight. Students’ learning processes are at the core and they must be involved in all parts – and throughout their studies.

That’s where it happens. Those young students contribute to transferring knowledge about how society as a whole thinks and understands the world. This needs to be integrated into both teaching and research.

It always starts with art!

Lars is happy to take the opportunity to showcase SSE’s art – a starting point for new conversations and new collaborations. For those lucky enough to get a private showing, the art tour offers not only a wide variety of art but also spontaneous meetings with staff as well as students. This becomes clear during our own tour, and several of the students we meet want to stay and talk to Lars. The pride of both Lars and the students is unmistakable.

The art not only reflects SSE’s level of ambition but also its approach to knowledge. For the past five years, students have also been able to take part in the Literary Agenda book circle to read and discuss fiction. These investments in the humanities form part of a broader pedagogical initiative to explore and develop new ways of teaching that also further self-cultivation. In an age of digitalisation and artificial intelligence, questions are particularly being raised on the skills or expertise employers need or seek to meet the future. Here, if art is not the answer, it may be the start of such conversations.

This text is translated from Swedish. Original text: Maria Grafström and Anna Jonsson. Photos: Sebastian Borg.

This article is part of the book “The Nuances of Knowledge – Stories About Collaboration”. The book is based on inspiring interviews with nine remarkable people who have managed to break down barriers between research and practice.