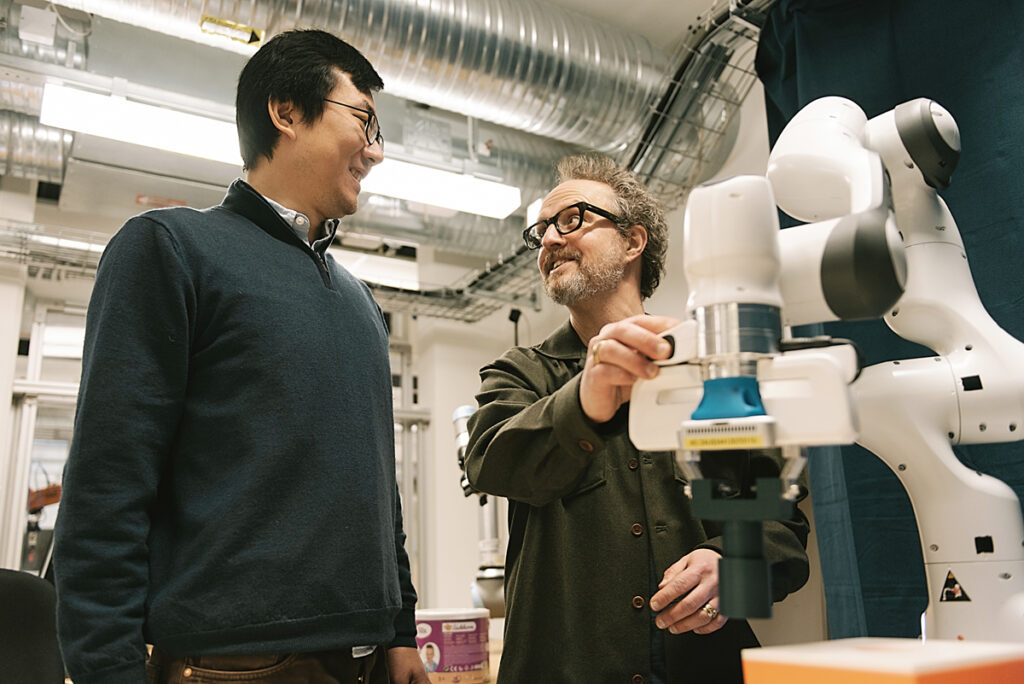

Johan Eker is the adjunct professor who became a “real” professor in an environment based on close collaboration between academia and industry. Thanks to support and encouragement from managers at both the Faculty of Engineering at Lund University and Ericsson Research, Johan has been able to be in the middle, with one foot in each world. It is a win-win model, but one that requires respect and the understanding that these are two different roles with different missions.

Johan Eker: Good people, a coffee machine, and a touch of madness

Johan Eker’s career can be seen as the result of collaboration between academia and industry, driven by a desire to work and contribute to both worlds. This also explains his roles both in the national Wallenberg AI, Autonomous Systems and Software Program (WASP) initiative, Sweden’s largest individual research programme aimed at strengthening “strategically motivated basic research” for the benefit of Swedish industry, and as chairman of the advisory group for the Internet of Things and People (IoTaP) – a research centre at Malmö University co-funded by the Knowledge Foundation. Johan describes these contexts as joint arenas for academia and industry to help each other understand what research might be relevant.

It’s a way for industry to influence the direction of academia, without controlling it. We in industry can inspire and demonstrate what is relevant by supporting research in a direction that is interesting to us.

At the same time, it is perhaps his understanding of the divide between academia and practice that has enabled Johan to be there “in the middle” and have both an academic career and one at Ericsson Research. Johan has of course also been helped by good managers who have allowed him to develop in both worlds.

The importance of happy accidents

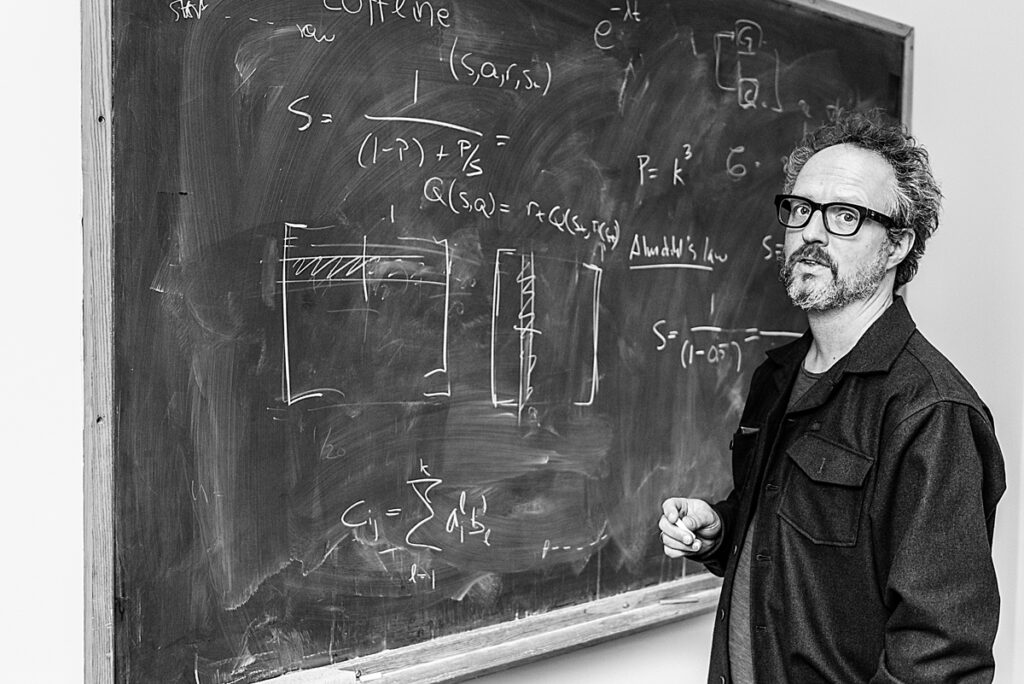

Academia’s task is to develop relevant questions, because it is much more difficult to ask a question than to come up with an answer. If you really know what you want from the outset, then industry can do it by itself without needing academic research. For Johan, research is therefore, in simple terms, about allowing competent people to develop good questions together.

I think that’s the hardest part of research – formulating a relevant question that no one else has asked. And often it’s a happy accident that leads to the question. Or as Pasteur said, ‘chance favours the prepared mind’!

Being able to develop good questions requires the time and conditions to think freely, without demands that it results in a deal and profitability. This is also the main difference between academia and business. When it comes to the ability to formulate relevant questions, it is not difficult to understand how Johan has managed to balance his roles. During our conversation, Johan asks questions in a way that allows him to reason his way to answers about why collaboration seems to be easy for some and more difficult for others. Johan’s reflections are pragmatic and based on the idea that most things in life require both and – but at the same time balance – whether it concerns research and practice, formal structure and unguided conversations, or work and leisure.

Dialogue broadens perspectives

Trusting and understanding the process, and not trying to control too much, is one of the reasons Johan gives for why his subject area – automatic control – lends itself so well to collaboration between academia and practice. What you learn along the way is often more important than the results themselves. Arguably, a doctoral student’s accumulated knowledge and experience are more valuable end products than the thesis itself. At the same time, this makes collaboration particularly difficult to measure. Johan and his colleagues excel at mathematics and are well able to do calculations; nevertheless, he reflects intriguingly on whether it is possible to measure collaboration.

I would say it’s almost impossible to measure. Because we do our projects and then we move on. And we’ve done two, three projects before they can be picked up and commercialised. And there may not even be anyone who remembers our involvement; for that to happen, there must be a patent or an article or something that gives guidance.

Patents are of course important to a company like Ericsson, just as in the rest of the telecoms industry. However, it often takes a long time to patent something, and it is not always easy to trace from whom or where the ideas come. As Johan points out, many years often elapse between presenting a research result and making a profit from it. Research therefore concerns having the courage to prioritise, allowing the work to take time, and sometimes permitting mistakes to be made. Johan reminds us that it is impossible to determine in advance what will be successful or contribute to important discoveries.

I often think of the Turing Prize winners in AI: Geoffrey Hinton, Yoshua Bengio, and Yann LeCun. They’ve been working on this since the 1980s and had their big breakthrough in 2011. All these people are still key figures in OpenAI and at Google and Facebook. They show that when you have really good people, you should invest in them and let them build their businesses.

The risk of “spreading too thinly” and not daring to invest in “really good people”, as Johan puts it, is that big breakthroughs will not see the light of day. It takes courage to trust your gut instinct and say “this is a good project; this seems like fun” without knowing exactly what you will get out of it.

The importance of context

The maturity of the industry, as well as the size of the company and its offer, affects the view of research and time, Johan reasons. In Sweden, we have had a tradition of research and development (R&D) departments at the larger industrial companies. Ericsson’s R&D activities are aimed at finding applications for new technology, which differs from how for example Google and Apple approach and view research. The latter often conducts more applied research with short-time perspectives, while a company like SAAB Gripen develops aeroplanes with a time horizon of 20 years or more. The temporal perspective also raises questions about the distribution of costs between academia and industry, says Johan.

If I put on my Ericsson hat, there’s a big difference in collaborating with the younger university colleges or universities, compared to perhaps Lund or KTH Royal Institute of Technology, which have slightly different profiles. At the younger universities, the groups are often smaller and more focused on applied research, I find.

Johan’s experience is also that there is often a greater willingness and enthusiasm to collaborate with local companies at the smaller university colleges or new universities, such as Malmö, Karlstad, and Örebro. And this is where funders such as Vinnova and the Knowledge Foundation play an important role. For older universities, and for those subject areas where collaboration is an integral part, collaboration comes more automatically and perhaps also attracts mainly the larger companies with resources to contribute, both in terms of expertise and funding. This probably creates, Johan reasons, different conditions for collaboration that ought to be kept in mind to understand what is involved.

Proximity creates momentum

Location is important in facilitating natural meetings. Johan describes the local environment in Lund as extremely favourable for collaboration. It is easy to move between the buildings that create a kind of food chain between the Faculty of Engineering, via the Ideon Science Park, over to the big companies – “just as it should be”. This proximity makes it possible to do degree projects at various companies and to give guest lectures, but also to build up a viable alumni organisation. It further creates a good base for companies to recruit talented employees.

To encourage researchers to move in the middle and between different worlds, Swedish universities could also operate more along the lines of the American model of sending their researchers on so-called internships at companies. According to Johan, this would be an easy way of creating pathways in and out of academia, which would also contribute to broader perspectives and new ideas.

Research within companies’ own R&D operations may also lead to collaboration with academia, as these researchers also publish in scientific journals. For Ericsson Research, such publications are important, says Johan, as they create legitimacy and act as examples of successful internal communication.

Space for the uncontrolled

For collaboration to be beneficial and add value, one needs to ask why it is necessary and who should be involved. Throughout the interview, Johan stresses the importance of time, trust, and clever people – and that too much micromanagement or conformity will lead to dreams and ideas going to waste. A touch of madness and bold ideas are also important.

I believe that if you put good people in a room to think about an important problem, and there’s coffee and food, great things will happen!

Signing a partnership agreement does not suffice – time, resources, and commitment are also needed. Often it takes firebrands to make it work. Johan emphasises the importance of giving space to soft values, so that people have the space to think and are able to last an entire career. This often characterises the Swedish work environment, and in some cases attracts foreign researchers and employees.

Research cannot be forced. Here Sweden is attractive. We may have to put up with the fact that we have much lower salaries, because if you go to Germany or the United States, you also face a lot more research control.

Freedom and flexibility also create space for other interests, such as creativity, which is not unimportant in this context. For Johan, this is expressed through a keen interest in music, and perhaps explains the easy-going, calm impression he conveys, despite having two careers. Perhaps another explanation lies in Johan’s ability to work with and elevate others. This approach also thrives in the culture focused on shared learning that permeates both the department at the Faculty of Engineering and Ericsson Research.

The invisible cost

Some subject areas require more collaboration than others. Collaboration is a kind of backbone for a subject such as automatic control, which has mathematics at its core and can be applied in a range of technological fields. Close collaboration between academia and practice is a prerequisite for the development of the subject and the industries that rely on science-based knowledge. The difference between university research and R&D at a company is that the latter always has an explicit business focus. For a company like Ericsson, with a research department comprising 800 employees, about half of whom have PhDs, research and development in academia and at the company go hand in hand. Johan describes it as almost self-sustaining – it does not have to be particularly complicated.

According to Johan, many companies make the mistake of thinking that they can make an initial contribution and that “something good will happen here in three years”, with the expectation that researchers will then present a solution. Yet it is seldom so simple. Instead, research and collaboration should be regarded as a continuous investment of time and commitment. Providing funding, a dataset, computing power, or something that is just “given” to researchers does not suffice. You have to engage. If you do not meet, nothing will come of it.

And this cost is somewhat invisible. It costs quite a lot to get involved, because you have to write articles together and it’s a bit more expensive than you’d expect, I think. But it’s also the only way to get any return on investment.

Without meetings and commitment – no return.

This text is translated from Swedish. Original text: Maria Grafström and Anna Jonsson. Photos: Sebastian Borg.

This article is part of the book “The Nuances of Knowledge – Stories About Collaboration”. The book is based on inspiring interviews with nine remarkable people who have managed to break down barriers between research and practice.