Cornelius Holtorf is a professor at Linnaeus University and describes himself as an archaeologist of the future. His interests range from preserving the memory of nuclear waste over time, to the kind of culture people are leaving behind for future generations, to addressing the climate crisis through cultural heritage. It is in collaboration with others that Cornelius says he can make a difference:

“I don’t just want to sit at the university and know all sorts of things.”

Already at the age of ten Cornelius Holtorf was enticed into the world of archaeology.

He was not just interested in digging for the remains of historic life on earth, but also in how everything in the world and in life is connected – in what it means to be human on earth. Today’s archaeologists need to look beyond “studying the ancient”, which is the Greek meaning of the word archaeology.

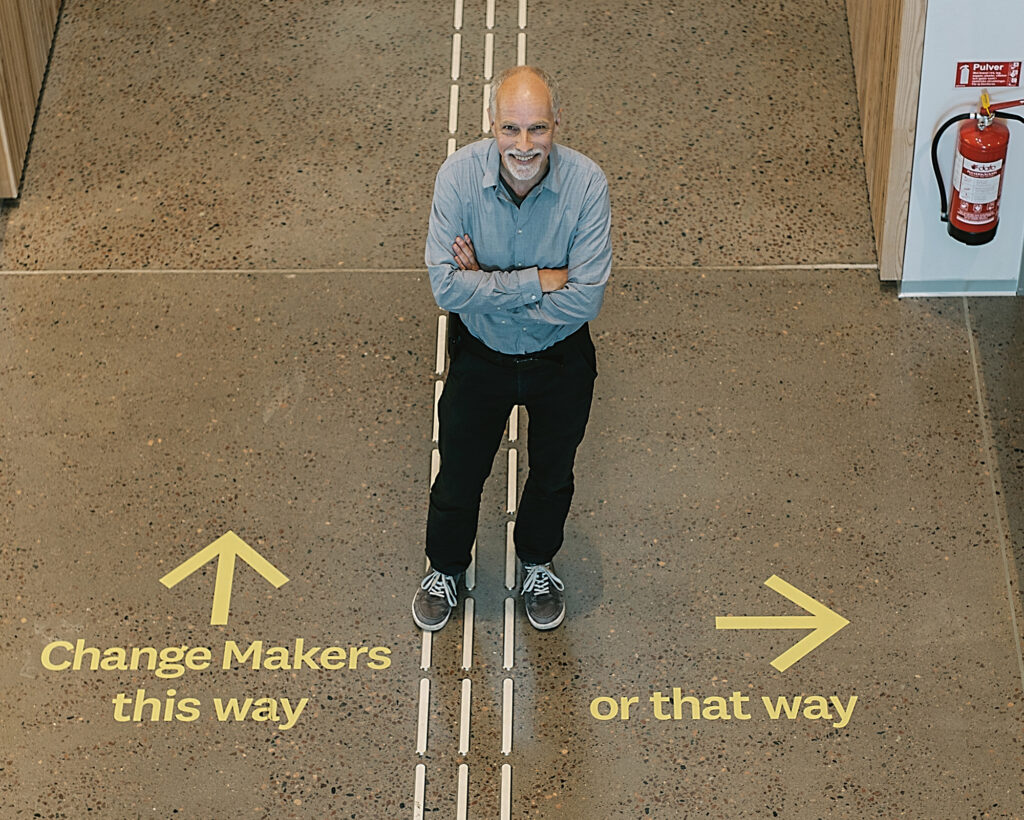

We archaeologists must learn to think big. Potentially, we can make a contribution to solving all global problems. Of course everyone can’t do everything, but it’s no longer enough to focus only on a specific question about the past or be uninterested in what others have to say about what we do. We are all part of society.

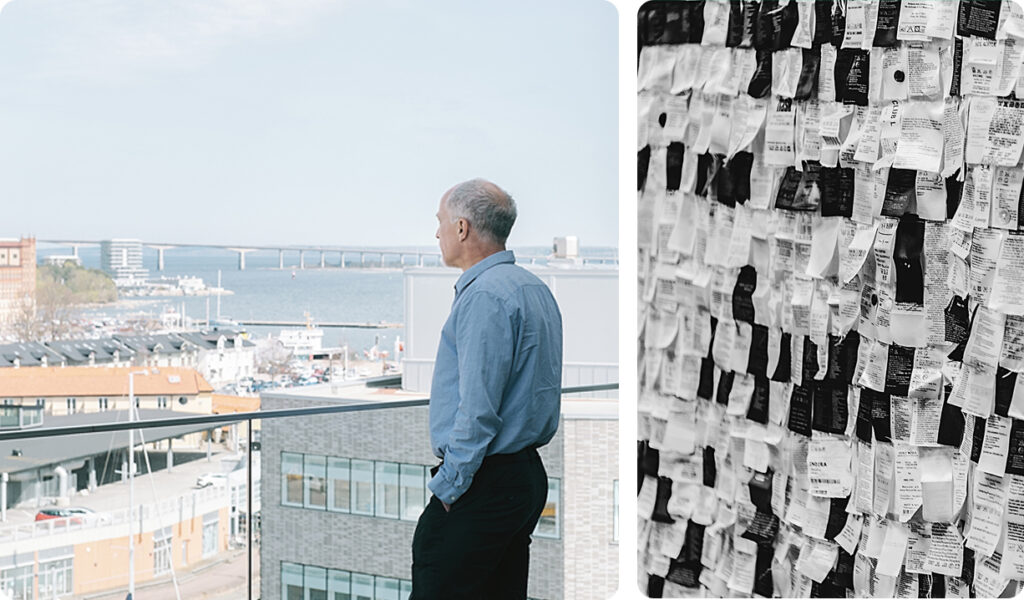

His interest in society, combined with his creativity and outspokenness, has led him to boundary-crossing dialogues and new places. From Germany, via Wales, Gothenburg, Cambridge, Stockholm, and Lund, he arrived at Kalmar and Linnaeus University in 2008. Here Cornelius has found a place where he feels at home. Perhaps it is the open and modern university building with a view of Kalmar Castle and the sea that contributes to the feeling of having a platform while at the same time being able to look out and forward.

When we first speak, Cornelius is at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles. He has just started a three-month stint as a guest scholar and is slowly settling into his new life. He sees international engagement as the path to change – difference can be made through multilateralism, a form of global collaboration between many partners. In this spirit he also holds a UNESCO Chair and explores the cultural heritage we will leave behind in the future.